By Enrique Saenz, Mirror Indy

Mirror Indy is a part of Free Press Indiana, a nonprofit news organization dedicated to ensuring all Hoosiers have access to the news and information they need.

Sandy Leeds remembers the glory days of West Indianapolis.

Now 80 years old, she was born in 1944 and lived in a post-war era she remembers as prosperous — her neighborhood a hot spot for manufacturing and other industries.

As a young girl, Leeds would watch her father set off for work at the Kingan and Co. meat packing plant on foot. The plant was located about a mile from the neighborhood until it burned down in the late 1960s.

But the proximity to work meant they were also close to the pollution being emitted out of smokestacks at facilities that surrounded the residential areas, like the former Reilly Tar & Chemical plant, the Olin Brass Indianapolis plant, the Chrysler Foundry and the General Motors stamping plant.

“We could smell the smoke,” Leeds remembered. “We could also smell other things that were going on, not knowing what they were, because this was normal and common.”

A new report by the Marion County Public Health Department suggests that the glory days of the west side came with a hidden cost for those who live there. The study found that residents on Indy’s near west side are more likely to develop lung disease or cancer. They’re also more likely than others across the county to visit the emergency room for breathing problems.

For Leeds, the report confirmed something she long feared. Some health problems are worse in her part of the city.

Her mother had Alzheimer’s disease, her father had lung cancer and, despite being a nonsmoker, she has lung damage that kept her hospitalized for nine days last year. She attributes her family’s health problems and those of many other neighborhood families to the area’s industrial past.

“This was more than 50 years ago, and yet I’m affected,” Leeds said. “When I’m working at home, all of a sudden my breathing gets worse, and I’m not doing anything.”

Higher risk for health problems

The meat packing plant where Leeds’ father worked was later transformed into White River State Park and Victory Field. But the area’s industrial legacy remains.

The neighborhood is home to some of the consistently highest emitters of particulate matter pollution, which is linked to decreased lung functions, an increased risk of heart problems, such as heart attacks and dementia.

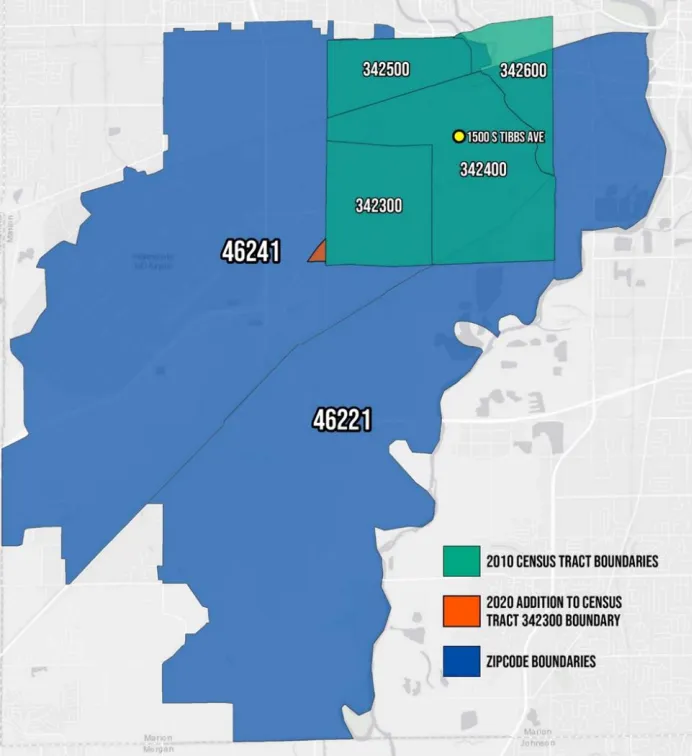

The department’s health assessment looked at hospital data from westside residents living in the 46241 and 46221 ZIP codes and four census tracts in between the two areas.

The study looked at the latest available data for hospitalizations for respiratory conditions, cancer, Alzheimer’s disease and dementia. All are conditions that are closely associated with environmental exposure to benzene, pyridines and ammonia — chemicals emitted by the former chemical plant at 1500 South Tibbs Avenue that closed last year. The plant is now the subject of an Environmental Protection Agency Superfund cleanup set to begin this summer.

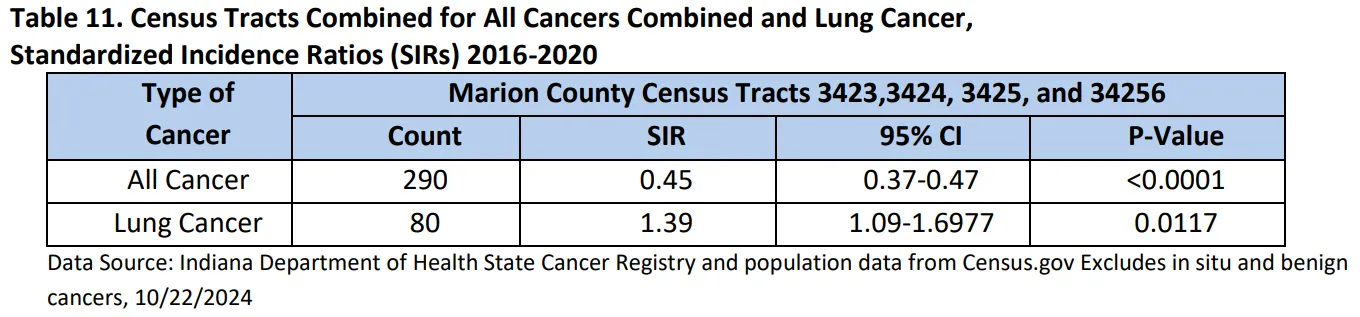

According to the report, the near westside area had a nearly 40% higher incidence rate of lung cancer diagnoses compared to the rest of the state between 2016 and 2020 and about a 39% higher lung cancer death rate than the rest of Marion County between 2003 and 2022.

The report also found a 28.5% higher rate of emergency room visits than the rest of the county between 2019 and 2023 for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, a lung condition that makes it difficult to breathe, and about a 20% higher rate of hospitalizations for lung cancer between 2017 and 2021.

But while many of these health problems are linked to industrial pollutants, the study itself stopped short of determining the cause.

Funding issues

Leeds wants to know what is causing the health disparities and how many people were affected over decades, but that’s not something the study addressed.

That type of study would take lots of money and time to accomplish.

“There’s always limitations with epidemiological studies, and that’s one of the challenges we have is, you know, there’s confounding variables, there’s biases, there’s difficulty in obtaining certain data. And you know, doing in-person surveys takes a massive amount of man hours,” said Jason Ravenscroft, administrator of the MCPHD Department of Water Quality and Hazardous Materials Management at a May 10 meeting of the West Indianapolis Neighborhood Congress.

Those types of studies were previously funded, at least in part, by federal environmental justice grants, but distribution of those grants are in danger due to the Trump administration’s rollback of diversity, equity, inclusion and accessibility initiatives.

As part of the rollback, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency closed the Office of Environmental Justice and External Civil Rights, which, among other things, helped distribute those grants. The EPA has also canceled nearly 800 environmental justice grants for things like pollution monitoring, prevention and cleanup in communities experiencing similar healthy disparities as West Indianapolis.

Help from the state also isn’t likely. A budget shortfall caused by lower than expected revenue largely due to the Trump administration’s tariffs and fears of a recession resulted in many cuts at the end of this year’s legislative session. That includes $60 million for the Health First Indiana program, which provides extra funding for local health departments across the state.

Gov. Mike Braun, a Republican, has also adopted a similar stance to Trump’s on environmental justice that could play a role in how the state regulates polluting industries in the future.

Braun issued an executive order on March 12 banning state officials from using considerations including race, ethnicity and educational attainment when making permitting, enforcement or grant decisions.

“Indiana’s environmental policy will be based solely on sound science — not a political agenda like ‘environmental justice,’ ” Braun said in a press release. “My environmental policy is all about preserving our abundant natural resources, fostering economic development and safeguarding Hoosiers’ health.”

But Janet McCabe, a former EPA deputy administrator during the Biden administration, says Trump and Braun’s understanding of environmental justice is based on faulty conclusions that could prevent potentially bad living conditions from getting better.

“Environmental justice reflects the fact that some people live in areas that are more polluted than other people, and that that’s not fair,” McCabe said. “It’s not about who they are. It’s not about how much money they make. It’s not about what color they are. It’s about (how) there is more pollution in their neighborhoods than other people have.”

What’s next?

Ravenscroft said the health department is looking into purchasing PurpleAir air quality monitors made to detect particulate matter pollution using a portion of a federal grant it received from the Biden administration. The number of air monitors that will be purchased and the location they would be placed is still being determined.

Need to report a polluter?

Residents can file an environmental complaint about a facility to the Indiana Department of Environmental Management online, by calling the department complaint coordinator at 800-451-6027 then selecting option 3 or by mailing a completed IDEM Complaint Form to the agency.

Mirror Indy, a nonprofit newsroom, is funded through grants and donations from individuals, foundations and organizations.

Mirror Indy reporter Enrique Saenz covers west Indianapolis. Contact him at 317-983-4203 or enrique.saenz@mirrorindy.org. Follow him on Bluesky at @enriquesaenz.bsky.social.

Catch more news at Great Lakes Now:

Neighbors worry development would raze urban forest

Why Indy won’t have curbside recycling until at least 2028

Featured image: An illustration compiles several images of industrial sites that contribute to pollution on the west side of Indianapolis. Credit: Illustration by Jenna Watson/Mirror Indy; Photos by Enrique Saenz and Jenna Watson/Mirror Indy

[php function=”remove_swift_shortcodes”]